Dario Argento

Master of the Macabre

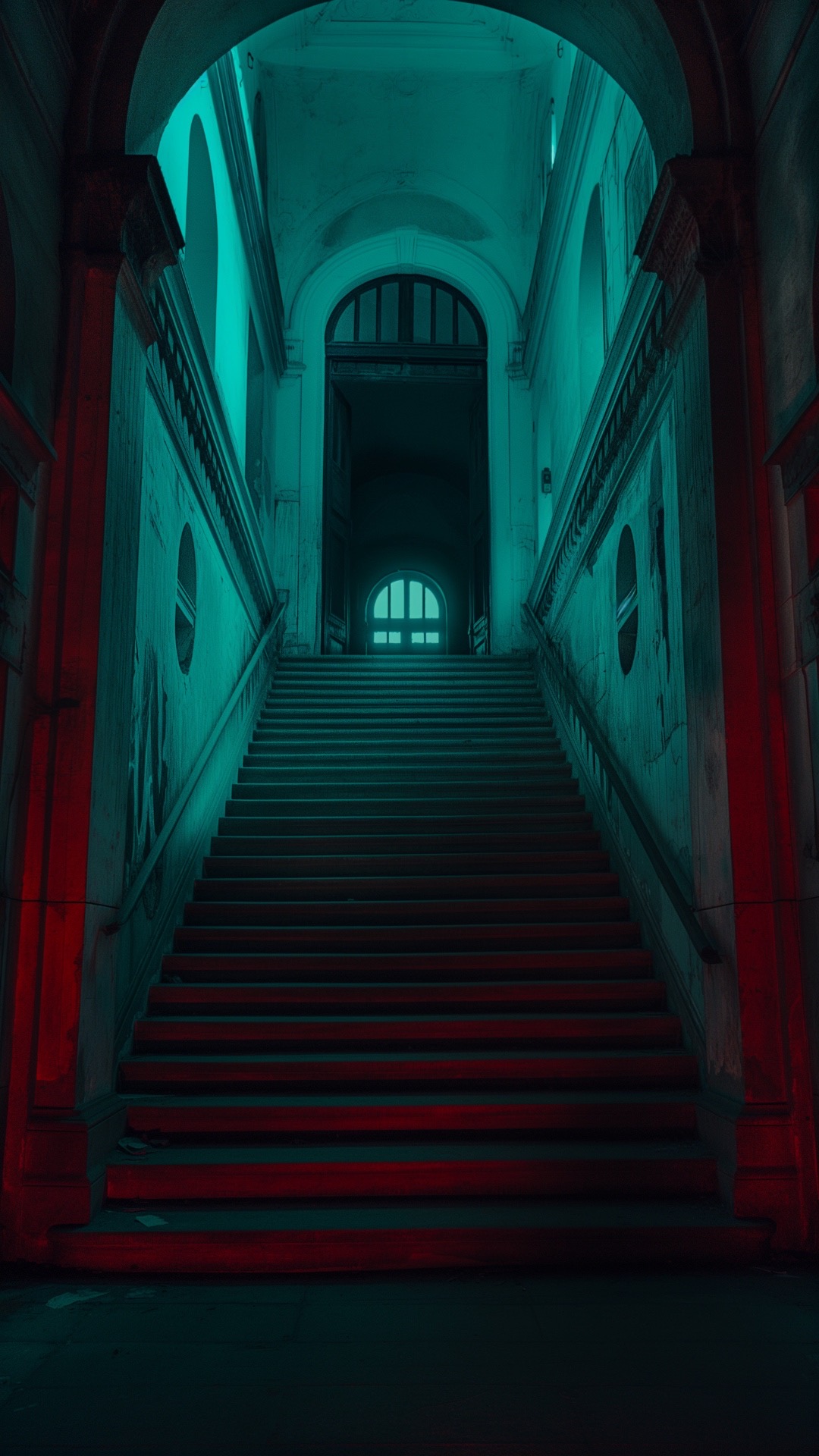

The Blade and the Palette

Few filmmakers have shaped the language of modern horror as decisively—or as stylishly—as Dario Argento. To speak his name is to invoke a cinema of knives and color, of whispered secrets and operatic violence, where murder becomes choreography and fear is heightened through sound, movement, and design. Argento is not merely a director; he is an architect of sensation, a filmmaker who turned horror into an immersive, almost musical experience. For Midnight Macabre’s Masters section, Argento stands as a cornerstone figure—one whose influence continues to bleed through contemporary genre cinema decades after his first film.

Rome, Critique, and the Eye

Born in Rome in 1940, Dario Argento was immersed early in a world of art and critique. His father, Salvatore Argento, was a respected film producer, while his mother, Elda Luxardo, was a renowned photographer. This dual exposure—to the mechanics of filmmaking and the aesthetics of visual composition—would define Argento’s career. Before stepping behind the camera, he worked as a film critic and screenwriter, developing a sharp understanding of cinematic structure and audience psychology. That analytical background would later inform his meticulous control over suspense and pacing.

Giallo Reborn

Argento burst onto the international stage with The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (1970), a film that did more than launch his career—it revitalized the Italian giallo genre. Giallo, traditionally a mix of mystery, crime, and lurid violence, became something more refined and more dangerous in Argento’s hands. He emphasized subjective camera work, elaborate murder set pieces, and unreliable perception. The viewer was no longer a passive observer; they were implicated, forced to see through the killer’s eyes or share the victim’s terror. This debut was followed by The Cat o’ Nine Tails (1971) and Four Flies on Grey Velvet (1971), forming an informal trilogy that established Argento as a director obsessed with memory, trauma, and the deadly consequences of mis-seeing the truth.

Deep Red, Permanent Damage

It was Deep Red (1975), however, that cemented his legend. Often cited as one of the greatest gialli ever made, the film combined a twisting mystery with brutal violence and an unforgettable progressive rock score by Goblin. Here, Argento perfected his signature style: long, gliding camera movements; bold, expressionistic color; and killings staged with an almost balletic precision. Deep Red also hinted at a shift in his work—from grounded mystery toward something more dreamlike and irrational.

Suspiria and the Terror of Color

That shift exploded fully into view with Suspiria (1977), arguably Argento’s most famous and influential film. Abandoning realism almost entirely, Suspiria plunges the audience into a fairy-tale nightmare of witches, cursed academies, and saturated primary colors. The film’s narrative logic is deliberately fragile; what matters instead is atmosphere. Argento used color like a weapon, bathing scenes in violent reds and icy blues, while Goblin’s pounding score assaults the senses. Suspiria redefined what horror could look and sound like, and its influence can be traced through everything from modern arthouse horror to music videos and fashion photography.

The Three Mothers

Argento continued exploring occult and supernatural themes in Inferno (1980) and later The Mother of Tears (2007), completing his “Three Mothers” trilogy—a loose mythological cycle centered on ancient, malevolent witches. While critical reception to his later work has been mixed, the ambition of these films underscores Argento’s lifelong refusal to play safe. Even when imperfect, his cinema remains fiercely personal.

Legacy, Influence, Bloodline

Beyond his directorial work, Argento’s impact extends through collaboration and legacy. He helped bring international attention to talents like Goblin and influenced generations of filmmakers, including John Carpenter, Guillermo del Toro, Nicolas Winding Refn, and countless others drawn to his fearless use of style and sensory overload. His daughter, Asia Argento, became a frequent collaborator and a notable figure in her own right, further entwining his legacy with the evolution of modern genre cinema.

Verdict

What ultimately defines Dario Argento is his belief that horror should be felt before it is understood. His films do not ask for logic; they demand surrender. Sound, color, movement, and violence combine into an overwhelming experience that bypasses intellect and strikes directly at the nervous system. In an era increasingly dominated by irony and restraint, Argento’s work stands as a reminder that horror can—and perhaps should—be excessive, beautiful, and dangerous.

For Midnight Macabre, Dario Argento is not simply a Master of the Macabre. He is a master of sensation itself: a filmmaker who taught audiences that fear, when crafted with artistry and audacity, can be as intoxicating as it is terrifying.