John Carpenter

Architect of Fear

Architect of Fear

If Dario Argento turned horror into a fever dream of color and movement, John Carpenter stripped it down to its bones—and discovered something far more chilling underneath. Carpenter is the great minimalist of modern horror, a filmmaker who understands that fear is most powerful when it is simple, patient, and inevitable. Across decades of work, he forged a cinema of cold precision: widescreen compositions, creeping dread, and electronic pulses that feel less like music and more like a heartbeat slowing to a stop. Few directors have exerted such a lasting influence with such apparent restraint.

Born in 1948 in Carthage, New York, John Carpenter grew up absorbing two formative influences: classic Hollywood genre films and modernist experimentation. He was drawn early to westerns, science fiction, and monster movies, but also to the clean visual logic of directors like Howard Hawks. That admiration would later crystallize into Carpenter’s guiding philosophy: clarity above all else. His films are never cluttered. Every frame, every sound, every cut serves the same goal—building tension with ruthless efficiency.

Carpenter studied film at the University of Southern California, where he made short films and developed the collaborative habits that would define his career. One of those early efforts, Dark Star (1974), began as a student project before expanding into a feature-length, low-budget science fiction comedy. While playful and uneven, it revealed two crucial traits: Carpenter’s comfort with genre mechanics and his ability to do a great deal with very little. That talent would soon reshape horror cinema.

The turning point came with Halloween (1978). Made on a shoestring budget, the film redefined terror not through excess, but through control. Carpenter’s camera glides calmly through suburban streets and domestic interiors, transforming safe spaces into zones of quiet menace. The killer, Michael Myers, is less a character than a force—silent, patient, unstoppable. Carpenter’s now-legendary score, composed by the director himself, is spare and repetitive, a musical embodiment of inevitability. Halloween did not just succeed; it rewired the genre, establishing the blueprint for the modern slasher while proving that atmosphere could be more frightening than gore.

Rather than repeating himself, Carpenter pivoted. The Fog (1980) wrapped ghostly horror in coastal atmosphere and campfire storytelling, while Escape from New York (1981) introduced audiences to Snake Plissken and fused dystopian science fiction with western archetypes. Carpenter’s heroes are often loners, professionals, or reluctant survivors—figures who understand the rules of the world too well to trust it. Authority, in Carpenter’s universe, is rarely benevolent. Institutions fail. Systems rot. Survival depends on individual resolve.

That mistrust reached its bleakest and most enduring expression in The Thing (1982). Initially misunderstood and commercially unsuccessful, the film has since been recognized as one of the greatest horror films ever made. Set in an Antarctic research station, The Thing is a study in paranoia, isolation, and the horror of not knowing who—or what—to trust. Carpenter’s direction is clinical, almost detached, allowing the tension to build through silence and suspicion. Ennio Morricone’s minimalist score pulses beneath the surface, while Rob Bottin’s groundbreaking practical effects deliver moments of shocking physical horror. Yet the true terror lies in the film’s existential question: if identity itself can be imitated and erased, what does survival even mean?

Throughout the 1980s, Carpenter continued to explore genre as a lens for social anxiety. Christine (1983) transformed a teenage coming-of-age story into a tale of obsession and control. Big Trouble in Little China (1986) gleefully subverted action-adventure tropes, while Prince of Darkness (1987) blended cosmic horror with quantum theory and religious dread. In They Live (1988), Carpenter delivered perhaps his most overtly political film—a savage satire of consumer culture and hidden power structures. With its iconic sunglasses and stark black-and-white imagery, the film distilled Carpenter’s worldview: the real horror is not monsters or aliens, but systems designed to keep people obedient and blind.

Despite his influence, Carpenter’s career has often existed at odds with mainstream success. Many of his films were initially dismissed or underperformed, only to be reclaimed later as classics. This pattern speaks to Carpenter’s refusal to chase trends. His films move at their own pace, demand attention, and resist easy catharsis. Endings are often ambiguous, victories provisional at best. Evil is rarely defeated—only delayed.

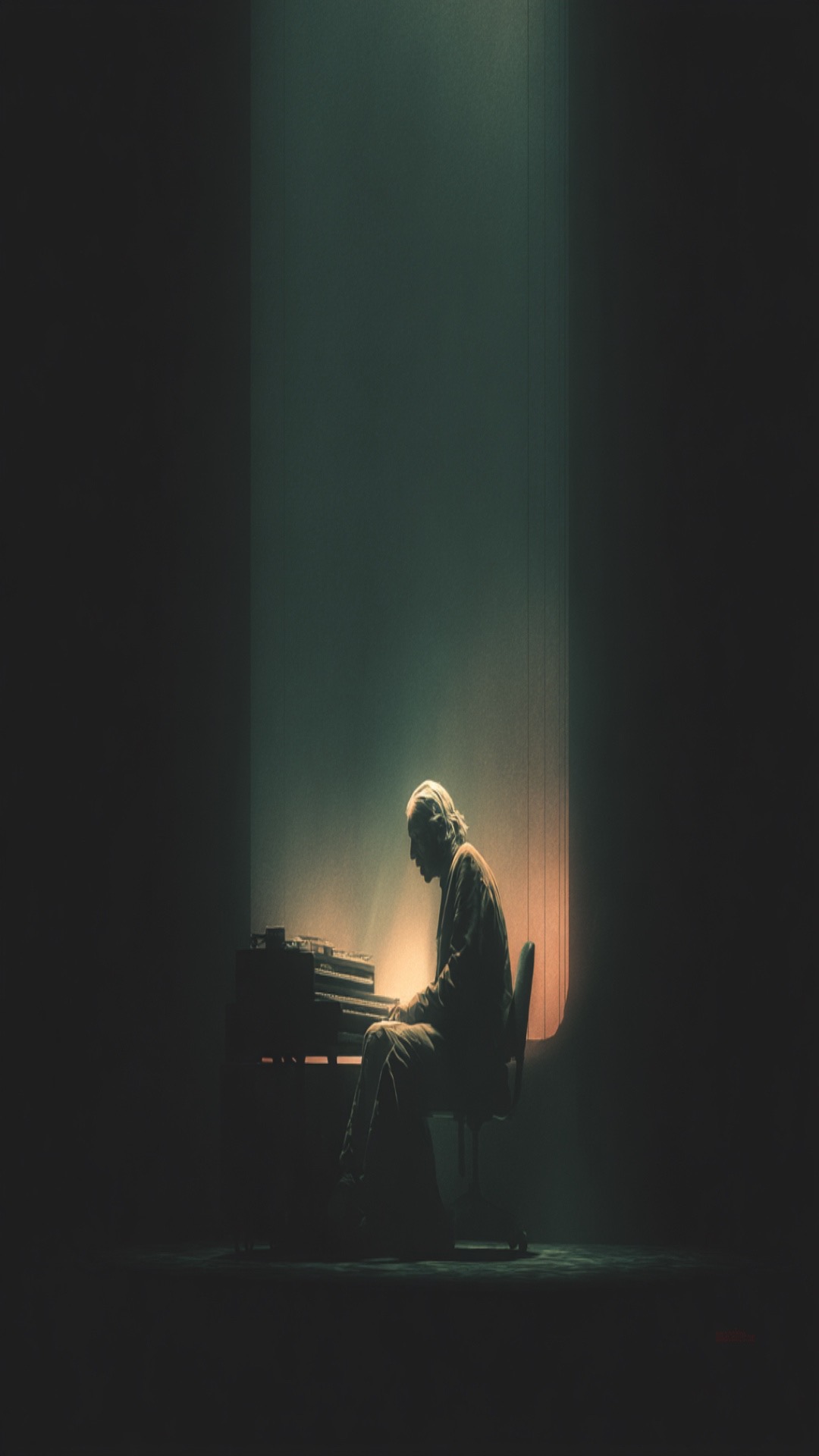

Beyond directing, Carpenter’s legacy is inseparable from his music. His synthesizer-driven scores are as iconic as his imagery, influencing generations of composers and artists across film, television, and electronic music. In recent years, Carpenter has embraced this aspect of his career fully, releasing albums and performing live, proving that his creative voice remains sharp and relevant.

John Carpenter’s cinema endures because it understands fear as a condition, not an event. His films do not rush. They wait. They watch. They let silence do the work. In an era of maximalism and excess, Carpenter’s restraint feels almost radical. He reminds us that horror does not need to scream—it only needs to get close and stay there.

For Midnight Macabre, John Carpenter stands as a Master not because he overwhelms the senses, but because he controls them. He is the architect of fear’s simplest, most enduring structures—and once you step inside them, there is no easy way out.